Toxic masculinity refers to certain aspects of traditional masculinity—being unemotional, aggressive, violent, etc.—becoming exaggerated to the point of being destructive. It stems from the (incorrect) idea that men who do not fit these traditional criteria are less masculine and thus of less value.

The term has become a buzzword due to some groups interpreting it as an attack on men themselves or a desire to eliminate the concept of masculinity entirely. This misunderstanding has led many men to rebuff the idea that toxic masculinity is dangerous, with a good few internalizing any criticism of it as criticism of themselves.

Toxic masculinity is a topic that has been spoofed time and time again in cinema, yet in so many instances the nuance goes over the audience’s heads. For a film to successfully satirize a topic, it requires a self-aware audience that is willing to look at the plot beyond what is on the surface. When the audience fails to comprehend the layers of a plot, the result is the idolization of movies like “American Psycho” and “Fight Club,” which are well-known as satirical works.

An article by Luke McMahan from Georgetown University’s student newspaper “The Hoya” refers to this as “literally me” cinema, in which hyper-masculine characters act with “aggression, misogyny and violence” out of “resentment and alienation,” which resonates with certain young, male viewers.

The 2000 movie “American Psycho” tells the story of Patrick Bateman (played by Christian Bale), a Wall Street investment banker and brutal murderer. The film — directed by Mary Harron — was adapted from Bret Easton Ellis’ 1991 novel of the same title. Bateman’s obsession with money, status and perfecting his image are intended to compensate for his lack of emotion and his feelings of inferiority. His violent behaviors are also motivated by low self-esteem and unemotionality. He is a caricature of “yuppie greed” and the worst parts of consumerism, corporate greed and masculinity.

Drawn to Bateman’s success and the respect he receives from those in his circle, the men who misunderstand the meaning behind the movie see him as a paragon of masculinity. This reverence is compounded by the fact that Bateman possesses this respect and the traits that are hallmarks of toxic masculinity while also being bizarre and antisocial. According to Bateman, no one will ever know who he really is beneath the figurative mask he wears, a sentiment that resonates with the young men who feel like he represents them.

Additionally, Bateman’s political beliefs favor those who are like him: white, straight, upper class and male. This is usually mirrored by the beliefs of those who find him aspirational, which is especially ironic considering “American Psycho” was written by a gay man and the film was adapted and directed by women.

Though there has been a recent uptick in this kind of thinking, this crucial misunderstanding is nothing new. When the film was first released, several investment bankers told Bale how much they enjoyed the movie unironically.

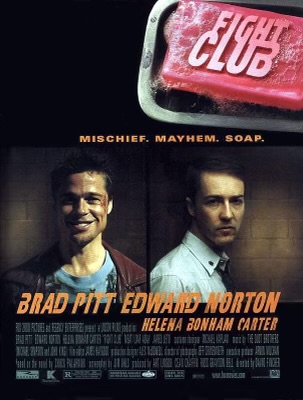

Similarly, David Fincher’s 1999 film “Fight Club” is often incorrectly viewed as a blueprint for masculinity, when it actually shows how damaging repression at the hands of the “American Dream” is. It follows the Narrator, who suffers from insomnia and is unsatisfied with his dull life until he meets Tyler Durden, a soap salesman, and the two start an underground fight club that eventually morphs into something much more dangerous.

Durden is strongly anti-establishment and anti-consumerism, and his nihilist views make the Narrator question his worldview. In expressing his views, he pushes the ideals of toxic masculinity: unemotionality, aggression and never showing any kind of “weakness.” To Tyler, fight club is meant to make men more masculine by feeling and inflicting pain.

His charisma makes other characters want to follow his example, but it also does the same to the audience. In the case of men who take cinema at face value, the presence of toxic masculinity in “Fight Club” is not condemning it, but promoting it.

Ignoring the fact that certain films are meant to act as cautionary tales rather than how-to’s undermines the director’s message. Movies like “Taxi Driver” and “The Wolf of Wall Street,” which depict the perils of obsessing over meeting standards of toxic masculinity, have suffered the same fate.

Men see these films as validation of toxic behaviors when they are the exact opposite, which leads to an increase in the kind of conduct that these movies seek to criticize.